A Note on Mask Registers

AVX-512 introduced eight so-called mask registers1, k02 through k7, which apply to most ALU operations and allow you to apply a zero-masking or merging3 operation on a per-element basis, speeding up code that would otherwise require extra blending operations in AVX2 and earlier.

If that single sentence doesn’t immediately indoctrinate you into the mask register religion, here’s a copy and paste from Wikipedia that should fill in the gaps and close the deal:

Most AVX-512 instructions may indicate one of 8 opmask registers (k0–k7). For instructions which use a mask register as an opmask, register

k0is special: a hardcoded constant used to indicate unmasked operations. For other operations, such as those that write to an opmask register or perform arithmetic or logical operations,k0is a functioning, valid register. In most instructions, the opmask is used to control which values are written to the destination. A flag controls the opmask behavior, which can either be “zero”, which zeros everything not selected by the mask, or “merge”, which leaves everything not selected untouched. The merge behavior is identical to the blend instructions.

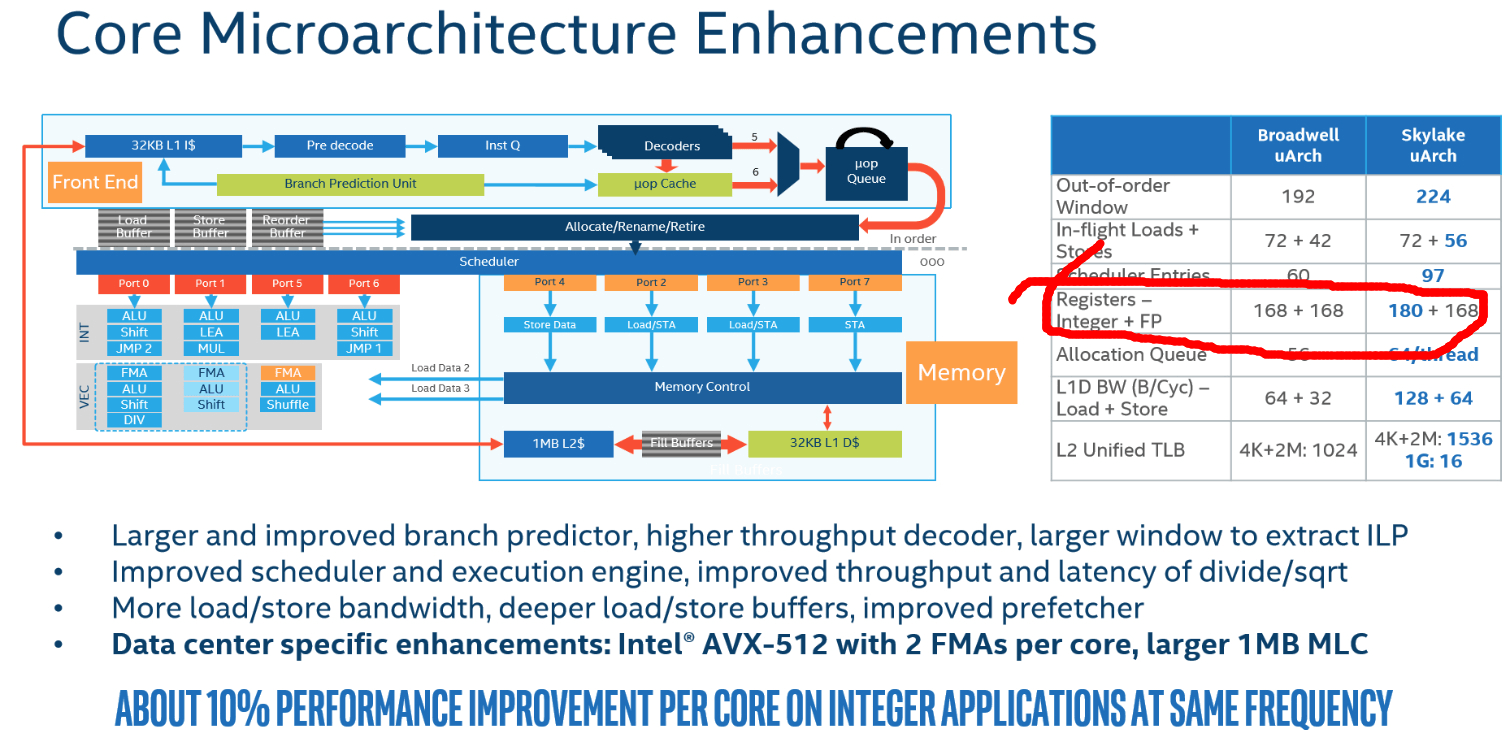

So mask registers4 are important, but are not household names unlike say general purpose registers (eax, rsi and friends) or SIMD registers (xmm0, ymm5, etc). They certainly aren’t going to show up on Intel slides disclosing the size of uarch resources, like these:

In particular, I don’t think the size of the mask register physical register file (PRF) has ever been reported. Let’s fix that today.

We use an updated version of the ROB size probing tool originally authored and described by Henry Wong5 (hereafter simply Henry), who used it to probe the size of various documented and undocumented out-of-order structures on earlier architecture. If you haven’t already read that post, stop now and do it. This post will be here when you get back.

You’ve already read Henry’s blog for a full description (right?), but for the naughty among you here’s the fast food version:

Fast Food Method of Operation

We separate two cache miss load instructions6 by a variable number of filler instructions which vary based on the CPU resource we are probing. When the number of filler instructions is small enough, the two cache misses execute in parallel and their latencies are overlapped so the total execution time is roughly7 as long as a single miss.

However, once the number of filler instructions reaches a critical threshold, all of the targeted resource are consumed and instruction allocation stalls before the second miss is issued and so the cache misses can no longer run in parallel. This causes the runtime to spike to about twice the baseline cache miss latency.

Finally, we ensure that each filler instruction consumes exactly one of the resource we are interested in, so that the location of the spike indicates the size of the underlying resource. For example, regular GP instructions usually consume one physical register from the GP PRF so are a good choice to measure the size of that resource.

Mask Register PRF Size

Here, we use instructions that write a mask register, so can measure the size of the mask register PRF.

To start, we use a series of kaddd k1, k2, k3 instructions, as such (shown for 16 filler instructions):

mov rcx,QWORD PTR [rcx] ; first cache miss load

kaddd k1,k2,k3

kaddd k1,k2,k3

kaddd k1,k2,k3

kaddd k1,k2,k3

kaddd k1,k2,k3

kaddd k1,k2,k3

kaddd k1,k2,k3

kaddd k1,k2,k3

kaddd k1,k2,k3

kaddd k1,k2,k3

kaddd k1,k2,k3

kaddd k1,k2,k3

kaddd k1,k2,k3

kaddd k1,k2,k3

kaddd k1,k2,k3

kaddd k1,k2,k3

mov rdx,QWORD PTR [rdx] ; second cache miss load

lfence ; stop issue until the above block completes

; this block is repeated 16 more times

Each kaddd instruction consumes one physical mask register. If number of filler instructions is equal to or less than the number of mask registers, we expect the misses to happen in parallel, otherwise the misses will be resolved serially. So we expect at that point to see a large spike in the running time.

That’s exactly what we see:

Let’s zoom in on the critical region, where the spike occurs:

Here we clearly see that the transition isn’t sharp – when the filler instruction count is between 130 and 134, we the runtime is intermediate: falling between the low and high levels. Henry calls this non ideal behavior and I have seen it repeatedly across many but not all of these resource size tests. The idea is that the hardware implementation doesn’t always allow all of the resources to be used as you approach the limit8 - sometimes you get to use every last resource, but in other cases you may hit the limit a few filler instructions before the theoretical limit.

Under this assumption, we want to look at the last (rightmost) point which is still faster than the slow performance level, since it indicates that sometimes that many resources are available, implying that at least that many are physically present. Here, we see that final point occurs at 134 filler instructions.

So we conclude that SKX has 134 physical registers available to hold speculative mask register values. As Henry indicates on the original post, it is likely that there are 8 physical registers dedicated to holding the non-speculative architectural state of the 8 mask registers, so our best guess at the total size of the mask register PRF is 142. That’s somewhat smaller than the GP PRF (180 entires) or the SIMD PRF (168 entries), but still quite large (see this table of out of order resource sizes for sizes on other platforms).

In particular, it is definitely large enough that you aren’t likely to run into this limit in practical code: it’s hard to imagine non-contrived code where almost 60%9 of the instructions write10 to mask registers, because that’s what you’d need to hit this limit.

Are They Distinct PRFs?

You may have noticed that so far I’m simply assuming that the mask register PRF is distinct from the others. I think this is highly likely, given the way mask registers are used and since they are part of a disjoint renaming domain11. It is also supported by the fact that that apparent mask register PFR size doesn’t match either the GP or SIMD PRF sizes, but we can go further and actually test it!

To do that, we use a similar test to the above, but with the filler instructions alternating between the same kaddd instruction as the original test and an instruction that uses either a GP or SIMD register. If the register file is shared, we expect to hit a limit at size of the PRF. If the PRFs are not shared, we expect that neither PRF limit will be hit, and we will instead hit a different limit such as the ROB size.

Test 29 alternates kaddd and scalar add instructions, like this:

mov rcx,QWORD PTR [rcx]

add ebx,ebx

kaddd k1,k2,k3

add esi,esi

kaddd k1,k2,k3

add ebx,ebx

kaddd k1,k2,k3

add esi,esi

kaddd k1,k2,k3

add ebx,ebx

kaddd k1,k2,k3

add esi,esi

kaddd k1,k2,k3

add ebx,ebx

kaddd k1,k2,k3

mov rdx,QWORD PTR [rdx]

lfence

Here’s the chart:

We see that the spike is at a filler count larger than the GP and PRF sizes. So we can conclude that the mask and GP PRFs are not shared.

Maybe the mask register is shared with the SIMD PRF? After all, mask registers are more closely associated with SIMD instructions than general purpose ones, so maybe there is some synergy there.

To check, here’s Test 35, which is similar to 29 except that it alternates between kaddd and vxorps, like so:

mov rcx,QWORD PTR [rcx]

vxorps ymm0,ymm0,ymm1

kaddd k1,k2,k3

vxorps ymm2,ymm2,ymm3

kaddd k1,k2,k3

vxorps ymm4,ymm4,ymm5

kaddd k1,k2,k3

vxorps ymm6,ymm6,ymm7

kaddd k1,k2,k3

vxorps ymm0,ymm0,ymm1

kaddd k1,k2,k3

vxorps ymm2,ymm2,ymm3

kaddd k1,k2,k3

vxorps ymm4,ymm4,ymm5

kaddd k1,k2,k3

mov rdx,QWORD PTR [rdx]

lfence

Here’s the corresponding chart:

The behavior is basically identical to the prior test, so we conclude that there is no direct sharing between the mask register and SIMD PRFs either.

This turned out not to be the end of the story. The mask registers are shared, just not with the general purpose or SSE/AVX register file. For all the details, see this follow up post.

An Unresolved Puzzle

Something we notice in both of the above tests, however, is that the spike seems to finish around 212 filler instructions. However, the ROB size for this microarchtiecture is 224. Is this just non ideal behavior as we saw earlier? Well we can test this by comparing against Test 4, which just uses nop instructions as the filler: these shouldn’t consume almost any resources beyond ROB entries. Here’s Test 4 (nop filer) versus Test 29 (alternating kaddd and scalar add):

The nop-using Test 4 nails the ROB size at exactly 224 (these charts are SVG so feel free to “View Image” and zoom in confirm). So it seems that we hit some other limit around 212 when we mix mask and GP registers, or when we mix mask and SIMD registers. In fact the same limit applies even between GP and SIMD registers, if we compare Test 4 and Test 21 (which mixes GP adds with SIMD vxorps):

Henry mentions a more extreme version of the same thing in the original blog entry, in the section also headed Unresolved Puzzle:

Sandy Bridge AVX or SSE interleaved with integer instructions seems to be limited to looking ahead ~147 instructions by something other than the ROB. Having tried other combinations (e.g., varying the ordering and proportion of AVX vs. integer instructions, inserting some NOPs into the mix), it seems as though both SSE/AVX and integer instructions consume registers from some form of shared pool, as the instruction window is always limited to around 147 regardless of how many of each type of instruction are used, as long as neither type exhausts its own PRF supply on its own.

Read the full section for all the details. The effect is similar here but smaller: we at least get 95% of the way to the ROB size, but still stop before it. It is possible the shared resource is related to register reclamation, e.g., the PRRT12 - a table which keeps track of which registers can be reclaimed when a given instruction retires.

Finally, we finish this party off with a few miscellaneous notes on mask registers, checking for parity with some features available to GP and SIMD registers.

Move Elimination

Both GP and SIMD registers are eligible for so-called move elimination. This means that a register to register move like mov eax, edx or vmovdqu ymm1, ymm2 can be eliminated at rename by “simply”13 pointing the destination register entry in the RAT to the same physical register as the source, without involving the ALU.

Let’s check if something like kmov k1, k2 also qualifies for move elimination. First, we check the chart for Test 28, where the filler instruction is kmovd k1, k2:

It looks exactly like Test 27 we saw earlier with kaddd. So we would suspect that physical registers are being consumed, unless we have happened to hit a different move-elimination related limit with exactly the same size and limiting behavior14.

Additional confirmation comes from uops.info which shows that all variants of mask to mask register kmov take one uop dispatched to p0. If the move is eliminated, we wouldn’t see any dispatched uops.

Therefore I conclude that register to register15 moves involving mask registers are not eliminated.

Dependency Breaking Idioms

The best way to set a GP register to zero in x86 is via the xor zeroing idiom: xor reg, reg. This works because any value xored with itself is zero. This is smaller (fewer instruction bytes) than the more obvious mov eax, 0, and also faster since the processor recognizes it as a zeroing idiom and performs the necessary work at rename16, so no ALU is involved and no uop is dispatched.

Furthermore, the idiom is dependency breaking: although xor reg1, reg2 in general depends on the value of both reg1 and reg2, in the special case that reg1 and reg2 are the same, there is no dependency as the result is zero regardless of the inputs. All modern x86 CPUs recognize this17 special case for xor. The same applies to SIMD versions of xor such as integer vpxor and floating point vxorps and vxorpd.

That background out of the way, a curious person might wonder if the kxor variants are treated the same way. Is kxorb k1, k1, k118 treated as a zeroing idiom?

This is actually two separate questions, since there are two aspects to zeroing idioms:

- Zero latency execution with no execution unit (elimination)

- Dependency breaking

Let’s look at each in turn.

Execution Elimination

So are zeroing xors like kxorb k1, k1, k1 executed at rename without latency and without needing an execution unit?

No.

Here, I don’t even have to do any work: uops.info has our back because they’ve performed this exact test and report a latency of 1 cycle and one p0 uop used. So we can conclude that zeroing xors of mask registers are not eliminated.

Dependency Breaking

Well maybe zeroing kxors are dependency breaking, even though they require an execution unit?

In this case, we can’t simply check uops.info. kxor is a one cycle latency instruction that runs only on a single execution port (p0), so we hit the interesting (?) case where a chain of kxor runs at the same speed regardless of whether the are dependent or independent: the throughput bottleneck of 1/cycle is the same as the latency bottleneck of 1/cycle!

Don’t worry, we’ve got other tricks up our sleeve. We can test this by constructing a tests which involve a kxor in a carried dependency chain with enough total latency so that the chain latency is the bottleneck. If the kxor carries a dependency, the runtime will be equal to the sum of the latencies in the chain. If the instruction is dependency breaking, the chain is broken and the different disconnected chains can overlap and performance will likely be limited by some throughput restriction (e.g., port contention). This could use a good diagram, but I’m not good at diagrams.

All the tests are in uarch bench, but I’ll show the key parts here.

First we get a baseline measurement for the latency of moving from a mask register to a GP register and back:

kmovb k0, eax

kmovb eax, k0

; repeated 127 more times

This pair clocks in19 at 4 cycles. It’s hard to know how to partition the latency between the two instructions: are they both 2 cycles or is there a 3-1 split one way or the other20, but for our purposes it doesn’t matter because we just care about the latency of the round-trip. Importantly, the post-based throughput limit of this sequence is 1/cycle, 4x faster than the latency limit, because each instruction goes to a different port (p5 and p0, respectively). This means we will be able to tease out latency effects independent of throughput.

Next, we throw a kxor into the chain that we know is not zeroing:

kmovb k0, eax

kxorb k0, k0, k1

kmovb eax, k0

; repeated 127 more times

Since we know kxorb has 1 cycle of latency, we expect to increase the latency to 5 cycles and that’s exactly what we measure (the first two tests shown):

** Running group avx512 : AVX512 stuff **

Benchmark Cycles Nanos

kreg-GP rountrip latency 4.00 1.25

kreg-GP roundtrip + nonzeroing kxorb 5.00 1.57

Finally, the key test:

kmovb k0, eax

kxorb k0, k0, k0

kmovb eax, k0

; repeated 127 more times

This has a zeroing kxorb k0, k0, k0. If it breaks the dependency on k0, it would mean that the kmovb eax, k0 no longer depends on the earlier kmovb k0, eax, and the carried chain is broken and we’d see a lower cycle time.

Drumroll…

We measure this at the exact same 5.0 cycles as the prior example:

** Running group avx512 : AVX512 stuff **

Benchmark Cycles Nanos

kreg-GP rountrip latency 4.00 1.25

kreg-GP roundtrip + nonzeroing kxorb 5.00 1.57

kreg-GP roundtrip + zeroing kxorb 5.00 1.57

So we tentatively conclude that zeroing idioms aren’t recognized at all when they involve mask registers.

Finally, as a check on our logic, we use the following test which replaces the kxor with a kmov which we know is always dependency breaking:

kmovb k0, eax

kmovb k0, ecx

kmovb eax, k0

; repeated 127 more times

This is the final result shown in the output above, and it runs much more quickly at 2 cycles, bottlenecked on p5 (the two kmov k, r32 instructions both go only to p5):

** Running group avx512 : AVX512 stuff **

Benchmark Cycles Nanos

kreg-GP rountrip latency 4.00 1.25

kreg-GP roundtrip + nonzeroing kxorb 5.00 1.57

kreg-GP roundtrip + zeroing kxorb 5.00 1.57

kreg-GP roundtrip + mov from GP 2.00 0.63

So our experiment seems to check out.

Reproduction

You can reproduce these results yourself with the robsize binary on Linux or Windows (using WSL). The specific results for this article are also available as are the scripts used to collect them and generate the plots.

Summary

- SKX has a separate PRF for mask registers with a speculative size of 134 and an estimated total size of 142

- This is large enough compared to the other PRF size and the ROB to make it unlikely to be a bottleneck

- Mask registers are not eligible for move elimination

- Zeroing idioms21 in mask registers are not recognized for execution elimination or dependency breaking

Part II

I didn’t expect it to happen, but it did: there is a follow up post about mask registers, where we (roughly) confirm the register file size by looking at an image of a SKX CPU captured via microcope, and make an interesting discovery regarding sharing.

Comments

Discussion on Hacker News, Reddit (r/asm and r/programming) or Twitter.

Direct feedback also welcomed by email or as a GitHub issue.

Thanks

Daniel Lemire who provided access to the AVX-512 system I used for testing.

Henry Wong who wrote the original article which introduced me to this technique and graciously shared the code for his tool, which I now host on github.

Jeff Baker, Wojciech Muła for reporting typos.

Image credit: Kellogg’s Special K by Like_the_Grand_Canyon is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

If you liked this post, check out the homepage for others you might enjoy.

-

These mask registers are often called k registers or simply kregs based on their naming scheme. Rumor has it that this letter was chosen randomly only after a long and bloody naming battle between MFs. ↩

-

There is sometimes a misconception (until recently even on the AVX-512 wikipedia article) that

k0is not a normal mask register, but just a hardcoded indicator that no masking should be used. That’s not true:k0is a valid mask register and you can read and write to it with thek-prefixed instructions and SIMD instructions that write mask registers (e.g., any AVX-512 comparison. However, the encoding that would normally be used fork0as a writemask register in a SIMD operation indicates instead “no masking”, so the contents ofk0cannot be used for that purpose. ↩ -

The distinction being that a zero-masking operation results in zeroed destination elements at positions not selected by the mask, while merging leaves the existing elements in the destination register unchanged at those positions. As as side-effect this means that with merging, the destination register becomes a type of destructive source-destination register and there is an input dependency on this register. ↩

-

I’ll try to use the full term mask register here, but I may also use kreg a common nickname based on the labels

k0,k1, etc. So just mentally swap kreg for mask register if and when you see it (or vice-versa). ↩ -

H. Wong, Measuring Reorder Buffer Capacity, May, 2013. [Online]. Available: http://blog.stuffedcow.net/2013/05/measuring-rob-capacity/ ↩

-

Generally taking 100 to 300 cycles each (latency-wise). The wide range is because the cache miss wall clock time varies by a factor of about 2x, generally between 50 and 100 naneseconds, depending on platform and uarch details, and the CPU frequency varies by a factor of about 2.5x (say from 2 GHz to 5 GHz). However, on a given host, with equivalent TLB miss/hit behavior, we expect the time to be roughly constant. ↩

-

The reason I have to add roughly as a weasel word here is itself interesting. A glance at the charts shows that they are certainly not totally flat in either the fast or slow regions surrounding the spike. Rather there are various noticeable regions with distinct behavior and other artifacts: e.g., in Test 29 a very flat region up to about 104 filler instructions, followed by a bump and then a linearly ramping region up to the spike somewhat after 200 instructions. Some of those features are explicable by mentally (or actually) simulating the pipeline, which reveals that at some point the filler instructions will contribute (although only a cycle or so) to the runtime, but some features are still unexplained (for now). ↩

-

For example, a given rename slot may only be able to write a subset of all the RAT entries, and uses the first available. When the RAT is almost full, it is possible that none of the allowed entries are empty, so it is as if the structure is full even though some free entries remain, but accessible only to other uops. Since the allowed entries may be essentially random across iterations, this ends up with a more-or-less linear ramp between the low and high performance levels in the non-ideal region. ↩

-

The “60 percent” comes from 134 / 224, i.e., the speculative mask register PRF size, divided by the ROB size. The idea is that if you’ll hit the ROB size limit no matter what once you have 224 instructions in flight, so you’d need to have 60% of those instructions be mask register writes10 in order to hit the 134 limit first. Of course, you might also hit some other limit first, so even 60% might not be enough, but the ROB size puts a lower bound on this figure since it always applies. ↩

-

Importantly, only instructions which write a mask register consume a physical register. Instructions that simply read a mask register (e.g,. SIMD instructions using a writemask) do not consume a new physical mask register. ↩ ↩2

-

More renaming domains makes things easier on the renamer for a given number of input registers. That is, it is easier to rename 2 GP and 2 SIMD input registers (separate domains) than 4 GP registers. ↩

-

This is either the Physical Register Reclaim Table or Post Retirement Reclaim Table depending on who you ask. ↩

-

Of course, it is not actually so simple. For one, you now need to track these “move elimination sets” (sets of registers all pointing to the same physical register) in order to know when the physical register can be released (once the set is empty), and these sets are themselves a limited resource which must be tracked. Flags introduce another complication since flags are apparently stored along with the destination register, so the presence and liveness of the flags must be tracked as well. ↩

-

In particular, in the corresponding test for GP registers (Test 7), the chart looks very different as move elimination reduce the PRF demand down to almost zero and we get to the ROB limit. ↩

-

Note that I am not restricting my statement to moves between two mask registers only, but any registers. That is, moves between a GP registers and a mask registers are also not eliminated (the latter fact is obvious if consider than they use distinct register files, so move elimination seems impossible). ↩

-

Probably by pointing the entry in the RAT to a fixed, shared zero register, or setting a flag in the RAT that indicates it is zero. ↩

-

Although

xoris the most reliable, other idioms may be recognized as zeroing or dependency breaking idioms by some CPUs as well, e.g.,sub reg,regand evensbb reg, regwhich is not a zeroing idiom, but rather sets the value ofregto zero or -1 (all bits set) depending on the value of the carry flag. This doesn’t depend on the value ofregbut only the carry flag, and some CPUs recognize that and break the dependency. Agner’s microarchitecture guide covers the uarch-dependent support for these idioms very well. ↩ -

Note that only the two source registers really need to be the same: if

kxorb k1, k1, k1is treated as zeroing, I would expect the same forkxorb k1, k2, k2. ↩ -

Run all the tests in this section using

./uarch-bench.sh --test-name=avx512/*. ↩ -

This is why uops.info reports the latency for both

kmov r32, kandkmov k, 32as<= 3. They know the pair takes 4 cycles in total and under the assumption that each instruction must take at least one cycle the only thing you can really say is that each instruction takes at most 3 cycles. ↩ -

Technically, I only tested the xor zeroing idiom, but since that’s the groud-zero, most basic idiom we can pretty sure nothing else will be recognized as zeroing. I’m open to being proven wrong: the code is public and easy to modify to test whatever idiom you want. ↩

Comments

The reason CPU is hitting brakes at 95% fill of PRF could be because it reserves few entries for a 2nd thread if it support hyperthreading/SMT. Some out of order structures reserve few entries for forward progress as well, in the event one op comes in non-speculatively. But PRF allocation might not be out-of-order, so that might not apply here.

I made an error with my testing - I used Henry Wong’s method of

mov edi, [rdx + rdi * 4]kadddetcmov esi, [rdx + rsi * 4]kadddetc loop branchand added a lfence after the second mov, but forgot to remove the second group of filler instructions. After fixing it, I get similar results with both methods, but lfence is cleaner as you note. However, I only see 114 mask regs (kaddb) on the Xeon 8171M with either robsize or my own code. I get 126 with kaddd, but that’s still not 134. Perhaps there’s some weirdness with using a cloud VM.

Why is a load fence used here? I tried this experiment on SKX and see fewer mask regs if I don’t use a lfence. However, other structure sizes don’t seem to be affected (i.e. ALU scheduler size)

Hi Chester,

The rob-size tool supports two different modes: with and without lfence, based on the presence or absence of the

--lfencecommand line parameter.Using lfence is just a way of cleaning separating each iteration of the test: nothing crosses the lfence, so either the 2 loads go in parallel or they don’t.

Henry’s original version didn’t use lfence, so you just rely on the fact that the loads form two alternating dependency chains to avoid more than two loads overlapping.

IME the lfence approach produces a somewhat cleaner plot and approaches or matches exactly the known structure sizes in more cases, but the difference is usually small. There is some non-ideal behavior near the transition point for most structures.

How big is the gap you are seeing for kreg lfence mode?

The zero value for mask registers is all ones (i.e. no masking). What happens when you do xnorb to kill one?

Hi Robert,

Thanks for your comment. I did some tests with

xnorb k1, k1, k1and some variations, but didn’t find any anomalies. The instruction itself seems to execute like any otherxnorb(so no indication of a “ones idiom” in analogy with “zeroing idiom”), and when subsequently using it with masked AVX instructions, I didn’t find any difference. Of course, my tests were not exhaustive!In general, masked operations with D or Q element width execute in the same time as their unmasked counterparts, while B and W widths suffer a latency penalty: they always take at least 3 cycles (IIRC) even if the unmasked operation takes 1 cycle. Some have additional penalties: e.g., 512-bit byte-granular masked stores are significantly slower than any other granularity or width of stores.